Author: @steakhouse (equanimiti)

We’re building on the RSN Org proposal posted a few weeks ago and wanted to share some thoughts on tokenomics for Radicle:

Foundations of DePIN

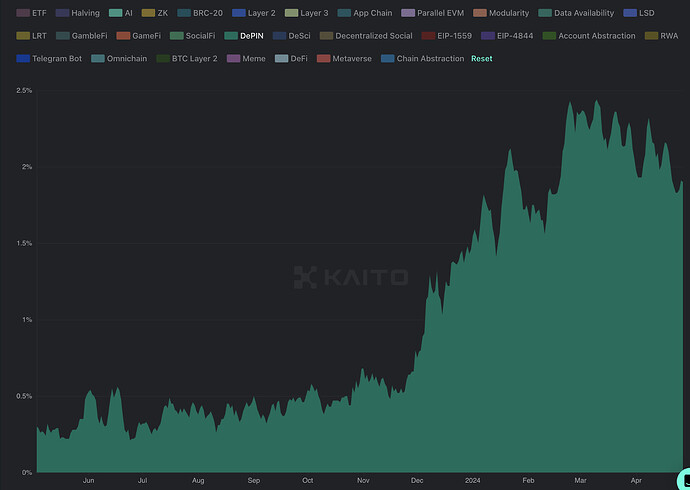

DePIN has become an increasingly important part of the wider crypto ecosystem and its mindshare. According to Kaito, in 2024, the category has risen from negligible levels to >2% of the entire market’s mindshare.

Source: Kaito

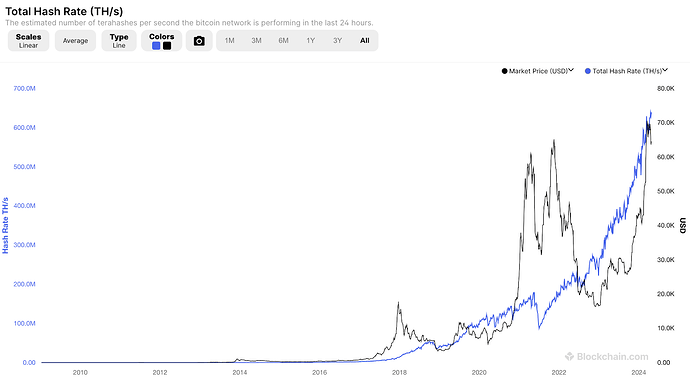

The most successful DePIN network to date is Bitcoin. By providing programmatic incentives to the miners, the Bitcoin network has achieved an impressive hash rate of 640 EH/s. This level of computing power is equivalent to that of 6.4 billion Nvidia RTX 4090s!

Source: Blockchain.com

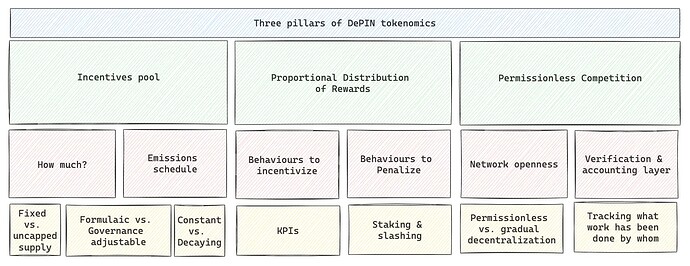

The follow-on DePIN projects have followed the foundational principles of Bitcoin’s success to bootstrap the supply-side of their respective network. The basic components are:

- A large incentives pool which follows either a time/block-based or a KPI-based emission schedule. Inspired by Bitcoin, many DePIN projects’ emissions follow some variation of a decay function

- Proportional distribution of rewards: Rewards are distributed proportional to some quantitative measure - hash rate in Bitcoin, stake in Ethereum, storage power in Filecoin. In the case of Saturn, rewards are based on a composite performance score (e.g. Time to First Byte, Bandwidth Served, Download Speed, Node Uptime)

- Permissionless competition: Open the network up to anyone to participate such that the level of service provision naturally improves as the network becomes more competitive

Various DePIN projects to date have made different design choices when implementing the three pillars. For instance, when determining the incentives pool, projects decide on parameters such as how much to incentivise, in what currency (token or fiat), and whether the emissions will be formulaic or governance-adjustable.

When determining the proportional distribution of rewards, the considerations are which behaviors to incentivize or penalize through slashing, if staking is enabled. The extent of the openness of the network could also vary. While Bitcoin and Ethereum have allowed permissionless entry from the beginning, Lido has taken a more progressive route to decentralization (e.g. a curated node operator module) in an effort to ensure a higher quality service in the bootstrapping stage of the network build out. Render is another DePIN project that is selectively onboarding supply.

In reality, the impact of the design choices that projects make to bootstrap a new economy and the associated trade-offs, are not very well understood. This is because many DePIN projects are still in their relatively early stages of experimentation. Even those that have somewhat successfully scaled their supply-side, such as Filecoin and Helium, have yet to achieve a sustainable level of demand.

DePIN mechanism design

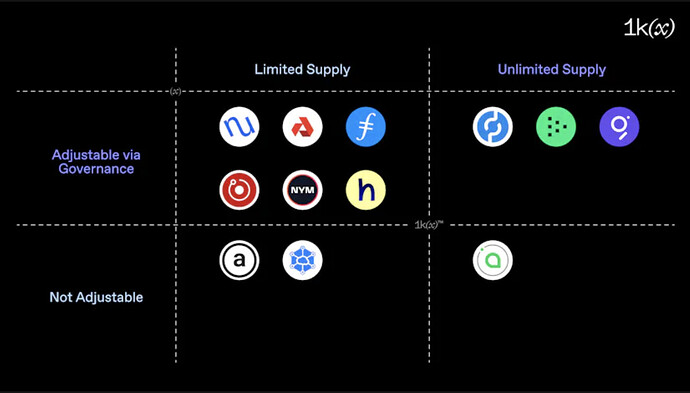

A comprehensive study undertaken by 1kx has explored the tokenomics design choices of DePIN projects. Projects can be generally categorized along four dimensions:

- Limited vs. unlimited supply: Limited supply has the benefit of enforcing a notion of token scarcity, but has the downside that the network should be successfully bootstrapped to reach a sustainable state before maximum supply is reached. From the projects’ perspective, fixed supply imposes a level of capital discipline (the do more with less mindset), but also could limit the flexibility necessary for growth. Bitcoin’s fixed supply tokenomics has set an odd precedent for the follow-on crypto networks

- Formulaic vs. governance-adjustable: A formulaic approach (e.g. BTC block rewards halving every 210k blocks) may gain social acceptance and an “immutability premium”, at the expense of inflexibility down the road. This approach places much pressure to get the tokenomics right at the start with incomplete understanding of a complex system. Conversely, adaptive methods through governance-adjustable mechanisms offer flexibility to make corrections over time as more information becomes available,though they may risk diminishing stakeholder trust if voting power is concentrated among the founding team and early investors.

- Constant vs. decaying rewards: Are the amount of emissions chosen constant or deflationary based on certain parameters, such as time or performance?

- Time/KPI-driven: Should emissions be purely based on time/blocks or depend on the state of the network such as node operator KPIs?

Source: 1kx

The above classification reveals two interesting trends.

- DePIN projects, likely inspired by Bitcoin, often follow a decaying token emission schedule that compensates early network participants more generously. The rewards decrease as the network matures

- However, unlike Bitcoin, most projects employ DAO governance for flexibility, allowing for adjustments but risking stakeholder acceptance with significant changes

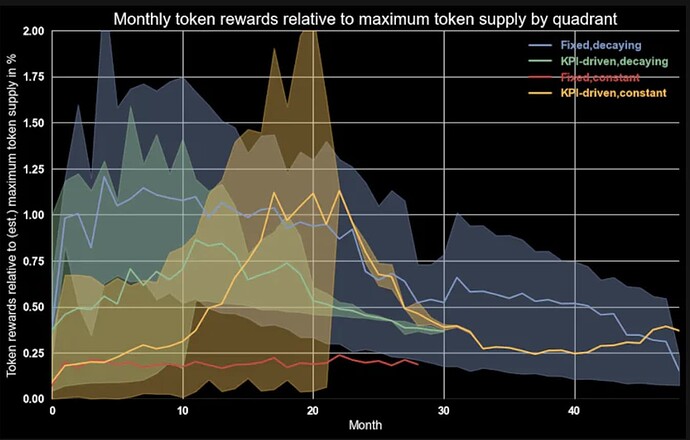

The study also shows monthly token inflation by emissions categories. Somewhat intuitively, the fixed, decaying model has the highest front-loaded inflation. Most DePIN projects reach peak token inflation in the first two years.

The Bitcoin-inspired model, while most followed by DePIN projects, have resulted in a few issues. In the next section, we investigate the outcomes from earlier projects and attempt to infer useful learning points or lessons.

Source: 1kx

Case Study: Filecoin

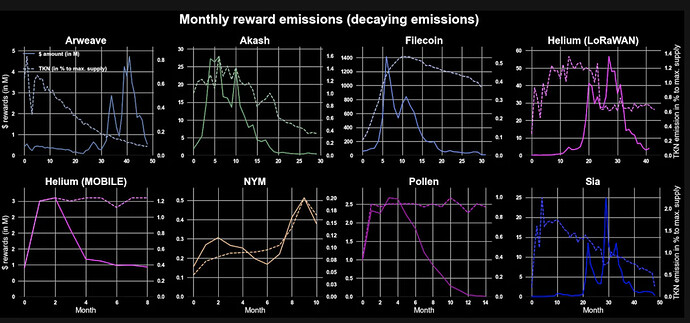

Filecoin is an OG DePIN project which has iterated on Bitcoin’s minting model. It employs hybrid minting, consisting of “Simple Minting”(30%) and “Baseline Minting” (70%).

- Simple Minting is the Bitcoin-like exponential decay, whereby 330m FIL tokens (out of max supply of nearly 2 billion FIL ) are released on a 6 year half-life based on time. This means 97% of tokens will be released over the next 30 years.

- Baseline Minting is KPI-based emissions. 770M FIL tokens are minted based on the capacity of the network. Baseline minting operates by comparing the network’s actual storage capacity to a predefined “baseline” storage capacity curve. If the network’s storage capacity meets or exceeds the baseline, new FIL tokens are minted at an optimal rate. If the actual storage is below the baseline, the minting rate decreases. All tokens will be released if the Filecoin network reaches a Yottabyte of storage capacity in under 20 years.

Filecoin’s hybrid emissions is arguably a step forward vs. simple minting, as baseline minting in theory should lead to increased creation of value for the network and lower risk of minting FIL too quickly. However, we observe two main weaknesses with the model:

-

Baseline minting still does not take into account the demand side of the network. During 1kx’s data sample period between October 2020 to April 2023, nearly 280M FIL (equivalent to $9.5 billion using monthly average FIL prices!) were distributed to the supply side. Lagging the time by a year, cumulative protocol revenues from October 2021 to April 2024 were 11.2M FIL (or $166m). The implied return on this “customer acquisition spend” was a mere 4.0% in FIL, or even worse at 1.7% in dollar terms. By not considering the demand response to the supply build out, Filecoin has so far shown poor returns on its incentivisation “investment.”

-

According to researchers from CryptoEconLab, accounting for demand in the tokenomics design has proven to be difficult due to a lack of reliable ways of reducing Sybil attacks. For instance, if KPIs related to data stored were to feature in the incentive design for storage providers (SPs), the optimal move could be to fake data storage in order to qualify for higher incentives.

-

Parameterisation of simple minting half-life. Part of the over-incentivisation that we’ve seen may be due to the fact that the 6 year half-life may have been too long. Juan Benet of protocol labs has said that if he could do the tokenomics again, he would shorten the half-life from 6 years to 2 years.

From the above, we take away early learnings about token-led DePIN economies:

- Study your demand: To create a sustainable economy, it is crucial to balance demand growth with token inflation used for supply growth. Can we anticipate who the users of the service offered by the network will be? Can we pace the rate of emissions to balance supply growth with demand growth better?

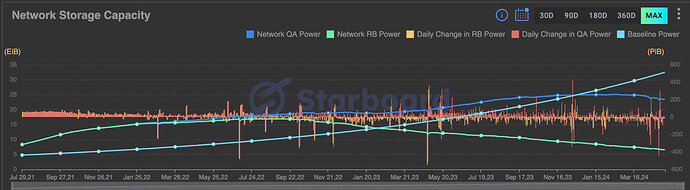

- There are risks with over-incentivisation: Highly favorable reward system could do more harm than good in drawing mercenary capital early on. Filecoin’s supply side (indicated by the green line, Network Raw Byte Power) grew rapidly and peaked in 2022. Since then, supply has been on a downward trajectory and has been undershooting the long-term baseline power target. Admittedly, FIL price cratering has not helped the attractiveness of being a storage provider. But one wonders to what extent, the earlier storage providers joined purely for incentive farming

Source: Starboard

FIL price (Source: Coinmarketcap)

- Study the cost base of the supply side: One practical solution that we see being effective for curbing overincentivsation and mercenary capital is designing incentives around the estimated cost base of the supply side.

Suppose a storage provider (SP) in Europe has an estimated cost base of $x, a SP in China has an estimated cost base of $0.8x, and a SP in America $1.4x. Could the reward program mint some amount of native token at each time interval that will cover the highest cost base supplier (i.e. $1.4x)?

- Consider rewarding the supply side in fiat pricing rather than in native token: A tokenomics researcher, Uroš Kalabić, who has peer reviewed the Helium’s Burn-and-Mint Equilibrium (BME) tokenomics goes a step further and suggests that the solution to the avoiding overincentivisation that risks crashing the network economy is simply by incentivising the supply side in stablecoins rather than the native token.

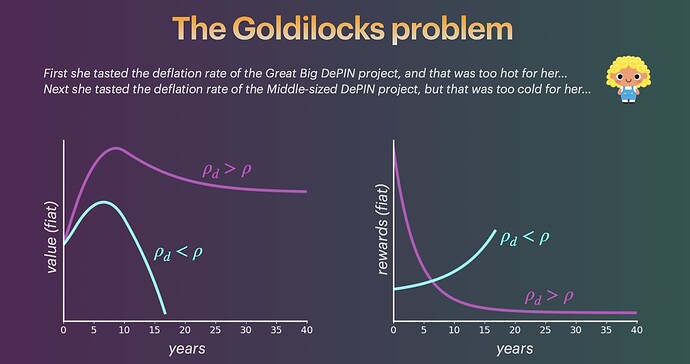

He describes the Burn-and-Mint-Equilibrium as a Goldilocks problem that needs to offer an optimal inflationary balance between the acceptability by the token holders and the supply side contributors. If the supply-side incentives are paid in the native token, the network runs into two possible scenarios:

- The purple line (undermint): Supply-side contributors do not receive enough incentives which decays in an exponential manner (right) and therefore the value of the network flatlines (left).

- The blue line (overmint): Conversely, the system provides too much to the contributors (right), that eventually the token holders abandon the network due to hyperinflation and the value goes to 0 (left)

Source: Uroš Kalabić

With some math, Kalabić concludes that the solution to the overmint/undermint Goldilocks problem is to price the mint rewards to contributors in fiat too.

The Radicle Seed Network (RSN)

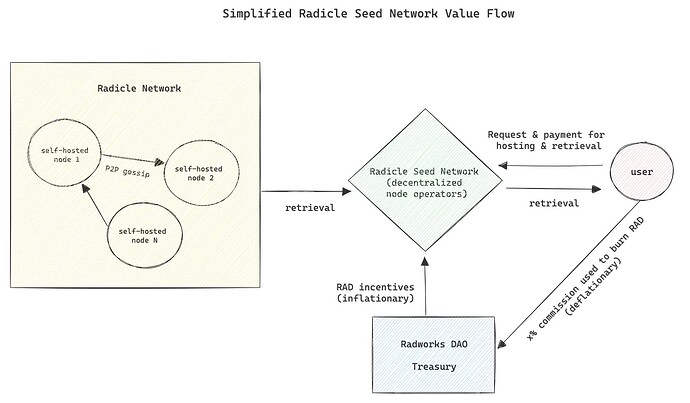

A simplified value flow of the Radicle Seed Network (RSN) look as follows:

The tokenomics group to consider the following aspects:

i) Understand supply-side cost base

- Define the hardware requirements

- Model the cost of running nodes

- Would the onboarding be permissionless or curated?

ii) Define KPIs to incentivise

- What metrics should be used to monitor “good performance”? (e.g. Bandwidth, Download Speed, Node Uptime).

- How do we easily verify these metrics?

- What is the right weighting formula between the KPIs?

iii) Define system penalties

- Do we enable staking and slashing? What are the pros and cons?

- Slashing criteria

iv) Understand demand side potential

- Who is likely to use this service? What would the user pay for such a service?

- What % of Radicle users would be interested?

v) Define the incentive pool and emissions schedule

- How much should be reserved for RSN incentives?

- Systematic vs. Governance-adjustable

- Decay vs. Fixed

- Fiat pricing vs. Token pricing

General Recommendations

- Tokens are a scarce resource - use them strategically and sparingly!

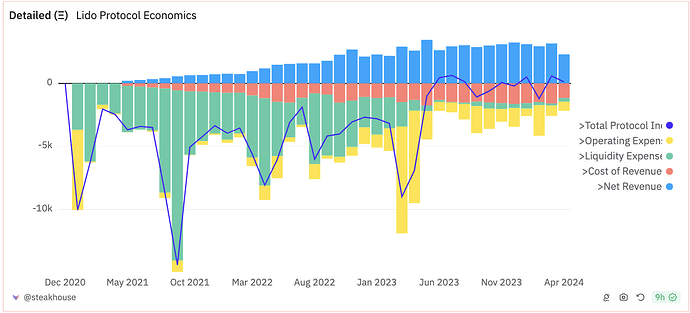

- Steakhouse played a pivotal role in preserving Lido DAO’s resources by recommending the discontinuation of $LDO incentives to LPs. Following our proposal, the DAO ceased these payouts without experiencing any loss in liquidity.

- Think about token incentives in the context of CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost). From the DAO’s perspective, we want the lowest CAC to successfully bootstrap a network that efficiently equilibrates the supply of node operators/service providers and demand

Source: Dune Analytics (@steakhouse)